I just ducked in to

The Ecologies Project at Monash Uni's Museum of Art. The exhibition is still being set up so I'll not give a full run down, just comment on a few works that caught my attention.

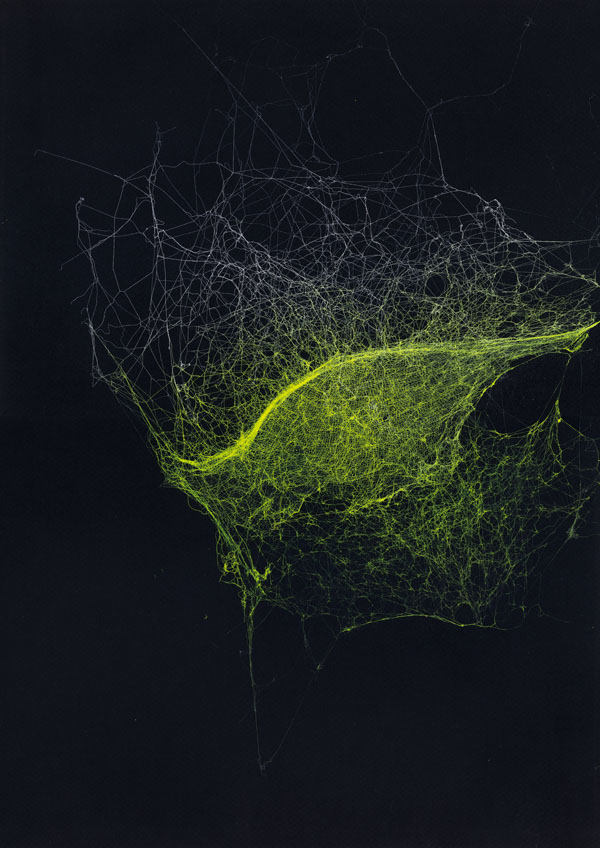

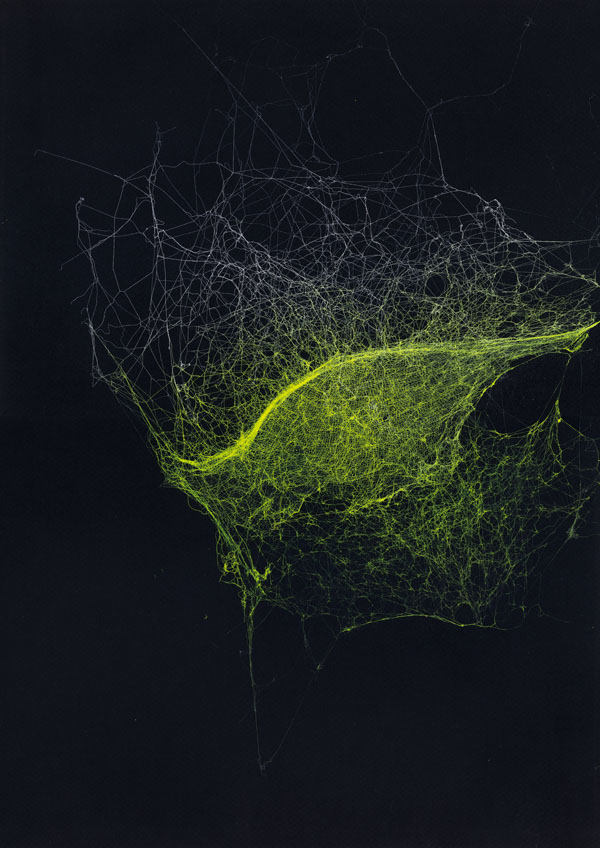

The first surprise was Sandra Selig's spider webs (image at left). Sorry, I don't know the name of the pieces — they didn't yet have a plaque. These are beautiful works, the kind of craft and aesthetics that makes me sit up and pay attention in a gallery. I was a little disappointed they were hung so high, they would reward detailed inspection. From a distance the webs appear to be interstellar clouds and have a liquidity about them that is resolved at close range into an infinity of fine thread. The luminous colours with which they are sprayed and the black background suggests that the artist too noted the potential vastness of these structures. "To see a world in a grain of sand... and all that Blakesque philosophy". Trite but true. A grey web on black has an elegance about it that the coloured forms lack. The sheen emerges instead from the varied density of the threads and the angle of the reflected light. All the same, these are lovely!

The similarity of patterns at multiple scales is a source of wonder for many scientists and artists. To see a spider's web as a colossal structure and an interstellar cloud as a tiny pattern in a lens is to muddle the usual perspective. A spider's web is an impenetrable, deadly thicket, a home, a nuisance that makes one's heart jump as it grabs at face and hair in the dark. This multi-level, visceral aspect of the thread is well captured in Selig's frames.

I'd never seen a decent print of Peter Dombrovskis'

Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, Tasmania (1979)... until now. This iconic image mobilised Australians as far away as Darwin to give a damn about a dam in Tasmania. It lifted the Australian conservation movement's impact up a notch and received global attention in some quarters. I place this image's cultural significance alongside the shot of blue Earth against the enormity of space. Both images reveal a world that was hidden. In each we see something worthy of protection.

The Franklin is an unseen place. Spectacular wilderness that is anything but mundane. For some, just the thought that places like this exist is necessary. Without them the world is somehow impoverished, albeit in a way that is often poorly articulated by those who have never experienced wilderness directly. (There I go complaining again about how others don't understand things as well as

I do. I must break this irritating habit!) In Dombrovskis' image the river is wild, powerful and primal. This water is not just "The Franklin", it is all wild rivers, even all wilderness and this

idea must be preserved. "No Dams", as a young high-school student this was (I think) the second time environmental issues appeared on my radar. The first was an effort to, "Save the Whales". I cannot recall any specific iconic image, only a pin badge I somehow acquired for the cause and non-specific footage of whales being slaughtered.

Morning Mist is no 20 cent pin badge. It is the kind of accessible spectacle that hangs as well on a gallery wall, a board-room alcove, or as a poster in a politically-aware share house.

The Earth from space is in many ways the counterpoint to the Franklin. It is the everyday Earth. The planet on which we live. But its bounds are rendered explicitly. Its fragility and above all its uniqueness, dominate the image. Not its strength. The Earth is not a symbol for all planets nor is it a concept, it is just

Our One Earth. On that globe all of humanity lives. All of history, all art and love and war. All the ecosystems of which we are a part share this tiny bubble in the enormity of the universe. Unlike the Franklin, the Earth is tiny, meek and mild. It is us, and we are alone. How pitiful, how insignificant are our battles. And yet, how vital it is that we fight them — from down here, the spider's web is a galaxy and we are flies trapped in it. We cannot escape to view our Earth from afar.

There's one more image (actually cinema footage) that immediately sprang to mind when I started considering

Morning Mist. That's the footage of the last

Thylacine pacing its cage in the Hobart Zoo (1930s). I've written about this footage before. A desperate animal, impatient, captive, the only thing certain is its death and the extinction of its kind. This sums up our colonisation of Australia, the way we treated its inhabitants and the way we continue to disrupt the ecosystems that have evolved here. We have a lot to be Sorry about.

Also in

The Ecologies Project was a wall-sized video projection of an open-cut mine shot from its floor. Trucks and diggers shunted rock around a whitened, dusty landscape. The pale powder had been spread around the gallery and a rather flimsy looking white sculpture reminiscent of a drill or over-head pump had been erected here also. This work troubled me somewhat. I think the idea has potential but it fell a bit flat on first viewing. The video lacked punch, the machines lacked energy, the footage was bleached and pale, perhaps to convey the dusty greyness of the mine, perhaps the projector was just not up to the task. The sculpture looked cheap and impotent beside the seductive moving imagery. Was this deliberate?

Whilst there were several works in the exhibition I really thought were weak, this

wasn't one of them. I just haven't worked out what I saw in it that kept me watching. I suspect that I have become so numbed by Hollywood's spectacular visual feats that video-art needs to pack a super-human punch to reach me or to take a completely different tack. At least the work wasn't a one-line gag!

The bleak minescape was certainly "interesting" but the video did not convey the awesome size of the site, nor the equipment, nor the immensity of the damage the mine symbolises. I think

The Eden Project's breath-taking and theatrical approach is far more thought-provoking (The Eden Project was built in an old open-cut mine.) The immensity of the Grand Canyon is far more awe-inspiring. This work needs to do more than depict something that is better experienced first hand.

Morning Mist succeeds where this fails because the photograph romanticises the wilderness. It takes the hard work, the biting cold, the mud and fierce rapids out of the river and leaves us with a symbol upon which to hang an imaginary wilderness. The mine footage takes all of the dust and noise out of the open-sore in the Earth, but I feel it leaves us with nothing and for this reason perhaps it failed to arrest me, despite my hope that it would.

I will revisit the gallery and see if I change my mind!

Crash. Until I'd read Ballard's book, I had no idea twisted metal, burning plastic and shattered bones could be considered by anybody to be erotic. I remember diving into the text on a flight home from Canada 15 years ago. The air hostess thought I was reading about aeroplane crashes... "Ahhh. Ummm. No. Actually the book is about sex in car accidents." I think that stunned her. She didn't pose any more questions apart from those she was paid to ask. "Tea or coffee?"

Crash. Until I'd read Ballard's book, I had no idea twisted metal, burning plastic and shattered bones could be considered by anybody to be erotic. I remember diving into the text on a flight home from Canada 15 years ago. The air hostess thought I was reading about aeroplane crashes... "Ahhh. Ummm. No. Actually the book is about sex in car accidents." I think that stunned her. She didn't pose any more questions apart from those she was paid to ask. "Tea or coffee?"