Agent-based models (ABMs) are computer simulations capable of accounting for differences in individual (human or other organism) attributes. They can be used to predict how circumstances involving many individuals interacting with one another and their environment might unfold under a range of scenarios. Questions an ABM simulation might help us to answer include, How would motor traffic operate if we add a new road from one city to another?; How would people vote in an election if we spread misinformation over online social networks?; How will this virus spread through our city?

Agent-based models (ABMs) are computer simulations capable of accounting for differences in individual (human or other organism) attributes. They can be used to predict how circumstances involving many individuals interacting with one another and their environment might unfold under a range of scenarios. Questions an ABM simulation might help us to answer include, How would motor traffic operate if we add a new road from one city to another?; How would people vote in an election if we spread misinformation over online social networks?; How will this virus spread through our city?

How do these simulations work? What makes them capable of prediction, and what are their limitations? How are they applied to understand a pandemic?

For clarity, I'll place ABMs into the specific realm of social and human behavioural simulation. Each individual (real) person has unique cultural, behavioural, physiological, psychological and physical attributes. These differences all impact the way we make decisions, and the way we interact with the world around us. ABMs take these individual differences into account by explicitly representing an "individual" and the historical conditions it has experienced, as well as the local conditions it is currently experiencing. Here's a simple example... if I fell off my bicycle and my twin sister did not, I may develop a fear of cycling that my sister does not develop, even though our upbringing, genetics and environment may be very similar. I would then be expected to make different decisions to my sister following the bicycle accident with regard to my assessment of cycling safety. This would impact my future interactions with the world around me in various circumstances. An ABM would explicitly model these different circumstances within an individual "agent" that forms part of a simulation containing many such agents that interact with one another and their environment. The simulation is in effect a complete "virtual world" full of independent agents that make decisions based on their past, their present situation, and their goals for the future.

One way to think about an ABM is as a large computer game, such as Pacman, with thousands of "ghosts" and no player-controlled Pacman character. Each ghost is an "agent" in the software that has its own position in the world, and its own goals, direction of travel, colour and history of interactions, relationships, movements and experiences. Each ghost moves around the virtual world meeting other ghosts, making decisions about what to do when it encounters another, or deciding which way to turn at a junction in the road. The observer just watches the game unfold but can also establish and alter the conditions under which the virtual world operates. They might state explicitly key attributes of the simulation in response to questions such as, How many ghosts are in the world? What are their properties? How big is the world? How are the roads connected? Then, once the world is established, the observer can see circumstances unfold with some semblance to how they unfold in the real world. This can be used to test out ideas about how to improve the world, stop the spread of a virus, save more lives, save more jobs, or preserve a nation's economy.

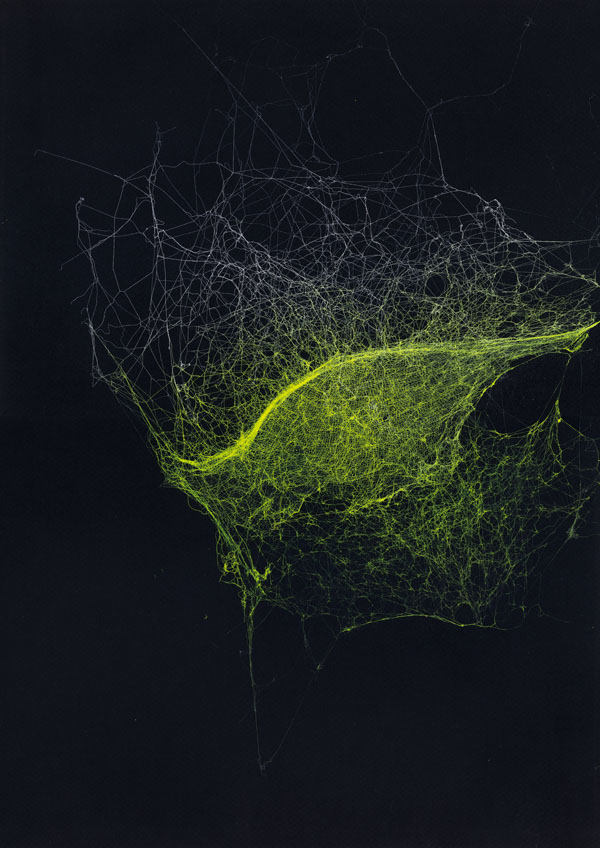

An ABM for modelling human interactions in a city might be realised as a virtual world full of human agents and non-agent infrastructure such as transport networks, schools, workplaces and homes. To understand how a pandemic spreads we could set up our world full of human agents that have tendencies to wear face masks, or not; tendencies to socially distance, or not; likelihoods to catch viruses, become contagious, and pass on viruses to other agents nearby. The world can have virus agents too - these might only exist within the bodies of a human agent but be passed from human agent to human agent by close contact. Adult human agents in the virtual world might live in households with other children and adult agents of different genders and ages. They might go to work during the day, travelling on virtual transport networks and exposing them to situations where they come in close contact with agents from other households. This could put them at risk of catching a virus if the agent they meet is carrying one, but this will depend on how the two agents specifically handle the interaction - Were they wearing a face-mask during the meeting? Did they stay 1.5m apart? Was the carrier agent shouting or singing?

In building such a complex model, the modeller must always make decisions about what aspects of the real world can be left out. For instance, if eye colour is felt to be irrelevant to a pandemic, there'd be no need to worry about modelling it. Or if the clothing worn by a human was irrelevant, that too would not be modelled. The difficult trick is figuring out what must be included in the model, and what can be omitted. If a key feature of the world for understanding a situation is left out, the behaviour of the model will not bear a close resemblance to the real world system it is supposed to be modelling. For instance if the model doesn't include humans wearing face-masks, then we can't use it to understand what the difference is between a real world with face-masks and one without. Similarly, if we misrepresent the conditions under which a virus spreads (assuming it spreads by contact with droplets on surfaces instead of via aerosols perhaps), then the virtual virus will spread through a community in our model in a way differently to how it spreads in reality, making our model potentially misleading. Hence, our models need constant improvement as we come to understand more and more about the real world situation we are modelling.

ABMs are an extremely powerful way to help us understand the complexities of human interactions and disease spread. They require a lot of expertise to design, a lot of expertise to build and operate, a lot of expertise also to calibrate and validate against the real world. And their results need to be interpreted carefully by experts. They aren't a magic bullet, but they are proving extremely useful in the world's present situation. Without computer scientists and epidemiologists, the experts constructing, operating and interpreting these models, it's fair to say we'd be running blind when it comes to handling today's pandemic. Sadly, when people ignore the science, well... the ramifications are distressing to say the least.

Extra reading: Here is an Open Access research article (I co-authored with some of the people leading Australia's current pandemic response modelling some years back) explaining an agent-based model, Synthetic Population Dynamics: A Model of Household Demography. This will provide some detail for those wanting to see how researchers use an agent-based model of human behaviour. ABMs are also valuable in understanding ecological interactions, here's a research article (work by an ex-PhD student I supervised recently) ABM simulating bee-flower interactions A-Bees See: A Simulation to Assess Social Bee Visual Attention During Complex Search Tasks.